9.25.23

The waves crash against the rocks with the violence of an old testament god, moving with a fury of creation and destruction intertwining in the surf. But the divine forces before me share none of the jealousy or wrath of those old bible stories. The Pacific Ocean is too old to have been created in our image and I don't believe it knows about these things. I think of all the places along its coast I've been and how different this unfathomable body of water has seemed from each. And yet, it's always seemed to me to be of one soul--an unchanging singularity, no matter how many versions of itself I've seen. It's there in its vastness, in its perpetual returning to the shore, in its all-seeing promise of having the answers--if only I would learn how to listen. We can't control the ocean any more than we can control life. Both were here before us and they will be here long after. We're just here to swim in their waters for a time, to be moved by their currents, and, perhaps, to learn how to ride their waves. I stand a few feet above the high mark of the tide and watch in awe, humbled by my inability to capture everything I'm feeling in words or an image.

6.09.23

Working at my desk yesterday, a neighbor stopped in front of the window off to my side. She crouched down for a while, then got up and left. She returned a little while later and, once again, crouched down under my window.

Stepping out to investigate, I found she’d discovered a little hummingbird on the ground in the bed of succulents next to my front door.

It was small, even for a hummingbird. The little bird blinked at us but made no attempt to fly away. I’ve seldom seen a hummingbird not in motion and never on the ground. Something seemed to be the matter.

My neighbor had gone to get a small dish, filled with sugar water. She’d read that hummingbirds can expend so much energy they find themselves too weak to get to a source of food and die. We stepped away, fearing our presence would keep it from feeding off the bowl she'd left and hoping that was all it needed to take flight.

Back inside, I saw two larger hummingbirds dart around the smaller one. One of the larger ones fed it something from its mouth. The bigger picture started to take shape. This little hummingbird was the fledgling of the larger two. They were keeping an eye on him from nearby perches and would occasionally fly down, trying to show him the way or help him along somehow.

We didn’t know if there was something wrong with the little hummingbird or if this was just part of the hummingbird process. What we did know was that there were four community cats that made our courtyard their home and, as long as this little bird was on the ground, it was living in danger.

So, with gloved hands, we carefully moved the little hummingbird and its supply of sugar water to a hanging planter, out of the reach of potential predators. This lasted only a few minutes, then it awkwardly flew back down to the ground. A few similar attempts were made in different locations, but all with the same result. The little bird, unaware of the danger, clearly preferred the ground to anywhere safer we tried to place him and we realized there were limits to how much we could, or even should, interfere.

But we kept an eye on him, each of us venturing outside to check on his well-being from time to time. Lauren came home and stayed near him for a while, wary of leaving him in the open without a guardian. I shepherded the cats to the gardens in the back lower level and hoped for the best.

Word of the little hummingbird spread among our neighbors, who cheered him on in text messages sent from within the courtyard and places they were visiting several states away. Videos were posted in a group thread as he hopped around between our apartments, exploring the world at a ground level while his parents kept watch overhead.

Then, around 10pm, my neighbor, the one who’d originally discovered him, sent word of the little hummingbird’s demise. Two possums had discovered him in his vulnerable position while out on a nightly patrol. Without the ability to fly, he never stood a chance.

You can’t blame the possums. They were just doing what possums do and these are the ways of the natural world. But that doesn’t mean I wasn’t sad about what happened. I’d wanted the little hummingbird to beat the odds, I’d wanted him to make it.

I thought about that pang of sadness for that little bird today and what it meant. I don’t know how long he was alive, not very long I imagine. But for whatever amount of time, he’d come into the world and that in itself is a big deal. And he’d had others who’d become invested in his story, were pulling for him, and who were sad when he didn’t make it.

And maybe, in the final analysis, those are the only things that really matter: that we’re here, that we have others who see us as we are and become invested in the best outcome of our story, and that someone will miss us when we’re gone.

In sharing the news of his death, my neighbor referred to the little hummingbird as Nigel. I’m glad she gave him a name. Good night Nigel. In your short time here, know you got to experience some of the most valuable things this world has to offer.

3.26.23

A Eulogy

Written for my dad and read at the services for his passing…

The Charge of the Light Brigade

I

Half a league, half a league,

Half a league onward,

All in the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

“Forward, the Light Brigade!

Charge for the guns!” he said.

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

II

“Forward, the Light Brigade!”

Was there a man dismayed?

Not though the soldier knew

Someone had blundered.

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to do and die.

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

III

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon in front of them

Volleyed and thundered;

Stormed at with shot and shell,

Boldly they rode and well,

Into the jaws of Death,

Into the mouth of hell

Rode the six hundred.

IV

Flashed all their sabres bare,

Flashed as they turned in air

Sabring the gunners there,

Charging an army, while

All the world wondered.

Plunged in the battery-smoke

Right through the line they broke;

Cossack and Russian

Reeled from the sabre stroke

Shattered and sundered.

Then they rode back, but not

Not the six hundred.

V

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon behind them

Volleyed and thundered;

Stormed at with shot and shell,

While horse and hero fell.

They that had fought so well

Came through the jaws of Death,

Back from the mouth of hell,

All that was left of them,

Left of six hundred.

VI

When can their glory fade?

O the wild charge they made!

All the world wondered.

Honour the charge they made!

Honour the Light Brigade,

Noble six hundred!

::

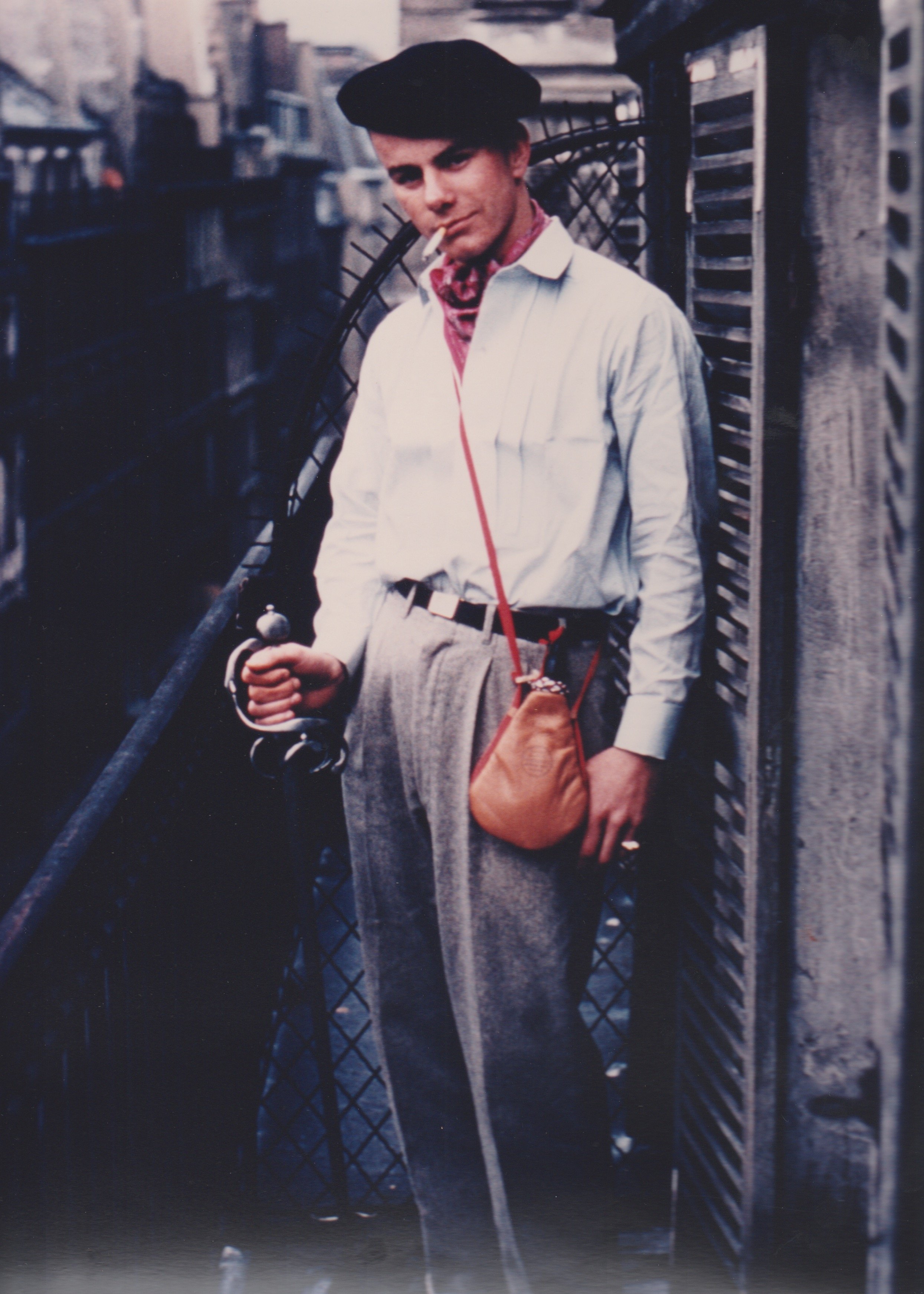

I flew here two Saturdays ago on a last-minute overnight flight, the prognosis for my father having made a dramatic turn for the worse and his condition rapidly declining. And in the liminal space of that flight, at an unknown hour somewhere over the middle of America, I knew I wanted to read this poem here to today.

But that’s not entirely true, because I think I’ve always known I’d read it on this occasion—not because it directly speaks to this moment, but simply because I knew my dad liked it and that I think he’d like knowing it was read in his honor, and because it reminds me so much of him.

I remember him sharing it with me as a child, first through the film, which starred his beloved Errol Flynn, and then later by actually reading the poem to me and telling me the story behind it. And it was through that sharing that I think I came to understand my dad a little more.

For those who don’t know, the charge of the light brigade was an act of incredible heroism born from a strategic military blunder. Bad intelligence and miscommunication sent a calvary into a battle they, being on the front lines, saw could not be won. And yet, when the order came down, they went anyway.

There’s a story from that day my dad told me where one of the soldiers who survived, being asked: “why? Why did you do it?”, simply replied, “because we’re British.” And I could see and feel in the emotion he had in telling me that story that it said everything for him—not specifically the British part of course, but the idea of it: the idea of a love and duty to something bigger than yourself, something you placed above your own wants, or even needs. And you can see that in the way my dad related to his country, his career, and, most importantly, those he loved.

Two Christmases ago I sat with my dad in the living room of my parents’ house. He’d become more aware I think of the limits of time and there were things he wanted to explain to me about his life, stories he said he hadn’t told anyone in sixty years. And in that conversation he talked about really just being a kid when he enlisted in the army: “You go from spending your whole life up to that point being taken care of by your family”, he said, “and then you join the army and they become the ones who take care of you, they’re sort of your family now.” And, with that, I understood a little more.

Because when someone asks you in the time ahead to describe my dad, “rule follower” is probably not anything that will come to mind—that my siblings and I even here speaks mostly to my dad’s uncanny ability to find his way out of the tight spots he sometimes created for himself.

And so it can seem counter intuitive in a way to square that streak in him with the institutions he served so well. But seeing the army, and then the fire department after it, as a kind of surrogate family—one that provided a sense of security, which is something I think he always sought—it all started to make sense and I got a clearer picture of the ways he learned to love.

But it was really coming on the final section of the poem that sealed my decision to read it here today:

When can their glory fade? Oh the wild charge they made!

My father made an absolutely wild charge through this life. And there’s so many stories I could insert here to support that. They’re there in every era of his life. But I know I don’t even need to explain that to any of you because, if you’re here, you already know the stories and, If you were lucky, you might even have been a part of some of them.

Oh the wild charge he made!

We all know it. And he did too…

The day we’d signed the papers for hospice I spent the night in his room, watching The Scarlet Pimpernel on my laptop next to him, an old movie we would watch together any time it came on TV while I was growing up. The next morning morning would be the last time I had to spend alone with him. He was no longer speaking but, on that morning, he was alert and, as I held his hand, he looked at me intently. As I sat there I read him that final section out loud:

O the wild charge they made! All the world wondered…

And I told him, “that’s you”. And, in that moment, he smiled at me in the way that was available to him —with his eyes: a mischievous glint that said, “Yeah, it was.”

In mourning the loss of his son, the musician Nick Cave wrote:

It seems to me, that if we love, we grieve. That’s the deal. That’s the pact. Grief and love are forever intertwined. Grief is the terrible reminder of the depths of our love and, like love, grief is non-negotiable.

My dad was loved very much. And he will be missed very much. And I know I can’t bargain with the grief. But I can choose how I navigate it. And for me that means to honor the wild charge my dad made through this world for all the things he loved. May it be that way for you as well.

2.28.23

“I want to take it slowly, to absorb my lessons through the skin, to sometimes get stung.”

I read these words in an article recently. The woman who said them was talking about beekeeping. But, as a life philosophy to adopt, you could do a lot worse.

2.21.23

Sometimes I’ll come across a string of sentences or even a phrase—an idea—in a book that stuns me, stops me in my tracks. Sometimes it’s not even a new idea, just one whose power has been made more clear and profound through the author’s words.

On the last page of Susan Orlean’s “The Library Book” she writes that all the things that are wrong in the world seem conquered by one simple idea:

“Here I am, please tell me your story; here is my story, please listen.”

In the week since I first read the passage I haven’t stopped thinking about it.

“Here I am, please tell me your story; here is my story, please listen.”

While I can’t be fully certain of its abilities to conquer all that is wrong with the world—there is after all a lot that is very wrong—what I do know to be true is that at the very least it can bridge the divide, lessen the burden, and lighten the darkness all that is wrong carries.

“Here I am, please tell me your story; here is my story, please listen.”

I think of the place I’m posting this. I think of the internet and social media. In its infancy this is the promise social media offered: a place to tell and hear each other’s stories with near limitless reach. I wonder if there’s a way to quantify how often that actually happens. Humans are bonding creatures. The single greatest predictor of longevity is human connection. I wonder why we don’t choose it more often than we do.

I called it an idea but that’s not the right word. It’s an action. It requires doing, both in the telling and the listening. In the Red Hand Files, Nick Cave writes, “a good faith conversation begins with curiosity, gropes toward awakening and retires in mercy.” This seems like a good place to begin. To that list I would add courage and vulnerability. The act of telling your story is of course one of great vulnerability. But it takes another kind of vulnerability to truly listen, to allow someone’s story to penetrate in a way that it knows it has been recognized and accepted. And vulnerability in all its forms is always preceded by courage.

“Here I am, please tell me your story; here is my story, please listen.”

I think of this place I live: the city of Los Angeles and the idea of Hollywood, a place whose better self coalesced around this idea, or at least aspired to. I think of how many times my life has been changed when a film or piece of television lived up to that aspiration. I think about how many more times it’s happened through music and books. Most of all I think about the times it’s happened through a friend.

Earlier on the page Orlean’s talks about the kind of crazy courage it takes to tell a story and put it out into the world, to believe there’s actually someone on the other side waiting to receive it. She calls the whole endeavor “precious and foolish and brave”.

Maybe this resonates with me because my whole life has been about telling stories, from theatre to music to film to writing and on. Even the parties I threw were in their own way trying to bridge that divide. My hope is that I always stay that foolish. My hope is you do too.

“Here I am, please tell me your story; here is my story, please listen.”

12.17.22

There is a certain kind of character found in the stories Hollywood tells. They can be broadly seen as “man against the world” types, but this seems to miss the point. They’re not actually against the world. What they are is determined to live in it on their own terms and the world seems against that. These characters have lit up our imagination for generations and are among my favorites. Paul Newman in “Cool Hand Luke”, Steve McQueen in “Papillon”, Kirk Douglas in “Lonely are the Brave” all immediately come to mind.

But for all the stories of this type Hollywood has written, it’s hard to think of one more compelling than the one actually lived by P-22.

P-22 was first spotted in Griffith Park roughly around the same time I moved to LA, settling into nearby Hollywood. His story has inspired me since. In some ways, it feels interwoven with my own.

Like so many others in LA I felt a kinship with him. I felt invested in his existence and a genuine love and admiration for him and all he embodied.

P-22 represented the best of LA. Sadly, his life now seems to have been cut short by some of city’s more intractable problems. Los Angeles is defined by reinvention as much as anything else. P-22 showed us the both the possibility and dire necessity for coexistence. I hope we honor him by reinventing our city to better reflect all he taught us.

I don’t envy anyone who was involved in the decision to euthanize, even as I know they did the best thing they could for him.

It’s worth visiting P-22’s official Facebook page. Beth Pratt’s eulogy says it all better than I imagine anyone else could. But I at least wanted to type out a few words here acknowledging how much this amazing cat's story has meant to me.

RIP P-22.

We’ll carry your story with us, even as your presence in our city is deeply missed.

11.29.22

Back in my early childhood —before any form of on demand viewing had become a thing— watching the Wizard of Oz was an event. It was shown on TV exactly once a year and that was it: your one opportunity to see it. If you missed it or fell asleep, well, try again next year.

Its showing was tied in somehow to one of the bigger holidays, either Easter or Thanksgiving if I’m remembering correctly. I want to say it was Thanksgiving, but I might be making that association based on the time, years later, when I was in college, when my entire family —from my 80-something grandmother to my single digit cousins— sat together after Thanksgiving dinner and watched the Wizard of Oz with the sound off while Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon played in the background. But that’s another story for another time…

As a child, I was always looking to carve out my space. The characters I was drawn to in any book, show, or movie felt like extensions of myself and, by becoming “mine”, they would form the small spaces I could claim as my own in a world that often felt like it didn’t have any room for me.

If we’re talking Star Wars, it was Han Solo. If it’s superheroes, it was Batman. And if we’re talking about the Wizard of Oz, it’s the Scarecrow.

When I think of the anti heroes I’m drawn to in films and literature, as well as the ones I’m compelled to portray in my own work, my early identification with characters like Han Solo and Batman makes sense and maybe even seems a little obvious. But, until this morning, I never thought about why it was I chose the Scarecrow.

When Dorothy meets the Scarecrow he’s tormented: ridiculed by the very crows he’s meant to keep away. His problem, he explains to her, is that he doesn’t have a brain. Dorothy offers him hope: the Wizard she’s seeking to get home might be able to help him out as well. And so off they go —off to see the Wizard.

As I assume we all know, the Scarecrow gets his wish in the end (I’m not apologizing if this is actually a spoiler for you). But the resolution is not so much that he gets a brain as it is the Wizard allowing him to come into the power of the one he already has. How? By giving him a diploma:

“Where I come from we have universities, seats of great learning, where men go to become great thinkers and, when they come out, they think deep thoughts with no more brains than you have. But, they have one thing you haven’t got: a diploma.”

-The Great and Powerful Wizard of Oz

There are countless versions of a story that has been told and retold throughout time. It was a particular favorite of a professor of mine in college who taught theatre history. It goes something like this: a young hero needs to embark on a quest they believe will challenge them beyond their own abilities. To help them, a wizened elder gives them a magic trinket to protect them on their journey. With the trinket’s help they succeed in their quest and return victorious. But when they see the elder again they learn that the trinket itself never possessed any magic at all. The power was within them all along.

Broadly speaking, this is know as a maturation plot and it would seem that the Scarecrow’s arc fits neatly within this category. But is that really what happened? I don’t think it is. I think it had something different to say and that what that is is what drew me in as a child.

Despite all the resourcefulness he shows on their journey, it’s only when the Scarecrow is given the diploma that he actually finds his brain. Said another way: he becomes what he’s always wanted to be through those around him seeing him as he wished to be seen, with the diploma serving as their manifestation of saying, “Yes, this is what you are.”

From this reading of the story, the Scarecrow’s arc is ultimately about the people you surround yourself with. His own positive ending comes from leaving behind the crows who make him feel less than and joining with friends who hold him up for what he wants to be.

Often made to feel less than myself as a child, the thing I wanted most was to be seen in a different light. I chose the Scarecrow because I wanted his story. I wanted those around me to listen to all the extraordinary things I thought myself capable of and show in action that they believed them too.

I realize this is a very un-American take on the Wizard of Oz. I mean is there anything we Americans love more than the fan-fiction of the boot-strapping self-made man? I don’t say that to denigrate self-reliance. If I’ve learned anything in life it’s that you can never count on what other people are going to do. And, sometimes, giving yourself that diploma is the only option you have. When others fail you, all you’re left with is finding your own way through it. But your resourcefulness to find your way makes their failure no less real. We are not here to be obstacles for one another. It’s our duty to each other as humans to hold up the best of one another, not as we want them to be but based on their own self-definition.

The terrible truth is that most people don’t actually want the best version of you. They want the version of you that’s best for them. I don’t say that to be cynical. I say it to emphasize the importance of finding those few among the many that actually hold you up in the ways that matter to you.

So if you find yourself feeling like you’re constantly swimming up stream--like the world is pushing against your every want--maybe the first step isn’t to change your desires but rather to change the people around you.

I’ve spent a lot of my life stuck the field with the crows. I write this as an open invitation to anyone else who’d like to go see about a Wizard.

Who in the hell do you think you are? A super star? Well right you are!

-John Lennon

4.04.22

As part of a decidedly lazy Sunday afternoon, I finished Matthew Spektor’s excellent, “Always Crashing in the Same Car”, yesterday.

In the book’s final section, there is a quote from the writer, and former New York Times film critic, Renata Adler, that has stuck with me.

“There is probably no more valueless kind of communication than everyone’s always expressing opinions about everything. Not ideas, or feelings, or information —but opinions, which amount to little more than a long, unsubstantiated yes or no on every issue.”

Spektor follows the passage with his own thoughts,

“Even as I smile to think of this idea being loosed into the lion’s den of Twitter, I don’t think she’s wrong. And if it seems contrary—what is a newspaper critic’s job, if not to opine on things?—what Adler is actually advocating for is something more along the lines of judgment: responses that are more interior, and less hyperbolic. She knows what every honest person does, which is that most of us don’t know what we think most of the time, and that an opinion can be a way of preventing ourselves from ever finding out.”

Coming at the end of a week drenched in a seemingly-endless stream of ‘hot takes’, it felt like there was something there -- in both Adler and Spektor's thoughts-- that was worth staying on a moment.

I'm not bringing this to the table with any kind of fully-formed conclusion attached; if for no other reason than wrapping things up with a ‘hot take’ of my own would feel wildly antithetical.

But I am curious: how do you feel about it? Any ideas; or information to share?

3.10.22

The story we tell ourselves is that the ability to be an artist, in this lifetime, functions something like a lottery; mostly out of our control and with not very good odds. But the real truth is that it’s just a decision we make for ourselves when we’re ready to take responsibility for all it means. It’s a truth that’s every bit as mundane as it is frightening; until we’re ready for it not to be.

10.14.21

It’s been a while since I’ve written here.

I had big ambitions for this section when I had it added it to the website. I imagined something a lot more prolific. But, as John Lennon once said, life is what happens to you when you’re busy making other plans.

It may still become the version of itself I originally envisioned. It’s just not there yet.

But, I have been writing.

I write every day, of course. I’ve been on the, “morning pages”, regime -like so many others who’ve read The Artist’s Way at any point- for a few years now. Forty-seven volumes of notebooks tucked into my closet testify to my near-perfect attendance to the practice.

But that’s not the kind of writing I’m talking about here. In the time since my last entry, at the end of June, I’ve been writing a script.

“Of course you have.”, I hear a voice say.

“Isn’t everyone in LA ‘working’ on a script?”

I’m not immune to the sound of that voice. I know it’s tone, intimately. But I don’t subscribe to it. I see its derision as a kind of a skim-coat over a brittle structure.

I would hear a similar version back when I was still throwing parties in Detroit. “Everyone’s a DJ now.”, went the lament from a certain sector of old-schoolers.

Good. Everyone should be a DJ. Everyone should write a script. Everyone should compose a song and play a part.

Everyone has a perspective to share. Everyone has a story to tell. Let’s have all of it and leave it to the receiver to choose which call gets a response.

I don’t buy into the scarcity mindset that tries to limit the number of entries. I’m more in favor of the man in the arena than I am being on the side of those who point out when the strong man stumbles.

I realize I’m getting away from myself. This was not what I came here to write about. But, sometimes, a digression can’t help but assert itself.

This is what was actually on my mind when I sat down…

when I said, I’ve been writing a script, what I should have said was, I’ve written one. Past tense. I just finished the other day.

I’ve been wanting to create something new for myself and the idea for this particular story has been swirling around in my brain for a while; or, at least the DNA of it has.

It’s the first part of what is meant to be a limited series. And my mind thrills at imagining the possibilities for where the story might go from here. I have ideas. But it’s all still very much a discovery. And I’m absolutely in love with the process.

“But is it any good?”

I don’t know.

More importantly though, I’ve come to realize that answering that question isn’t my burden to carry.

As I went back through what I wrote, scene by scene, and doubted every aspect of it, I kept asking myself over and over, “Is it any good?”. And, over and over, the only answer I had was, “I like it.”

That’s it. That’s the only compass I have. That’s the only place I can work from.

What will happen from here? I don’t know. Whether or not it gets made, whether or not it gets seen, whether or not it gets jeered or applauded, that all falls on others, who now shoulder the responsibility of deciding, is it any good.

You are the jury. I am the defense. And I believe my client’s worthiness. I believe in their truth. And the whole of my argument comes down to this…

I like it.

I’ll leave the deliberations to you.

6.28.21

I’ve been thinking a lot about story; what it is, what it isn’t, and why and how it matters.

This current preoccupation is purely selfish. I’ve been trying to write a new script. My leap-frogging ambitions and sense of grandiosity stubbornly dictate that I follow a five-minute short film with a pilot for a fully-formed series.

And so I sit, day after day; often staring at my laptop screen as if it were the Dawn Wall. Dissatisfied with my rate of progress, I read various forms of writing about writing -hoping to find the “instructions for assembly” that correspond to the story in front of me.

I recently pulled Robert McKee’s, Story, off my shelf and came across the following passage.

A culture cannot evolve without honest, powerful storytelling. When society repeatedly experiences glossy, hollowed-out, pseudo-stories, it degenerates. We need true satires and tragedies, dramas and comedies that shine a clean light into the dingy corners of the human psyche and society. If not, as Yeats warned, “…the centre can not hold.”

I think about the times we’re living in now; where it seems clear the center is not holding. I then think about the ascendence of reality tv and influencers in our lifetime and the relation of their rise to the point McKee is trying to make. This, it all seems to say, is why story matters.

6.13.21

Ttéia 1, C | Lygia Pape

::

I went back to Hauser & Wirth yesterday to steal another moment with this piece.

Ttéia… a joining of the Portuguese words for a web and something or someone of grace.

Silver thread and light. Two elements executed beautifully. Sometimes, that’s all you need.

6.11.21

Last night, over dinner, I listened as someone agonized over a difficult choice.

He’d begun preparations for moving across the country in a month’s time. Reservations had been made. Deposits put down. The ball was already in motion. But he wasn’t ready to leave LA; and even less so California. In leaving though, there was an opportunity to finish an advanced degree and all that could mean.

I don’t envy the decision. There are any number of valid arguments on both sides of the divide. And I hold no qualifications to say which one he should choose. But there was something he said, when he’d reached a point in the conversation where it felt like the scales were tilting towards going, that caught my attention. The idea of it stuck with me; enough to write about it today.

“Otherwise, what will be the point of everything that’s happened?”

That’s the thing that hit me. In his saying it, it felt like the final destination that all the other arguments in favor of going were heading towards.

The “everything that’s happened” were a childhood of abuse and later-life struggles with addiction. The program he would be leaving this city for would result in a degree in social work. The idea here being that, by taking his trauma, and its resulting struggles, and using them to help others, it would help make sense of it all, by giving it a purpose -a means to do good.

Without that means and purpose, what would be the point of it all?

The nourishing effect of helping others is not to be underestimated. But how far does that actually go towards answering the question posed?

The simple fact is we live on a plane of existence where truly terrible things happen sometimes. And there never is a point to it. There’s no greater reason waiting to be discovered. No matter what you do to convert the pain into something beautiful, the ends will never justify the means.

That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try to create beauty from ugliness. To do so is probably the single bravest and most noble accomplishment in any lifetime. I also believe, sometimes, it’s simply a necessity for survival.

But there will never be a point where you will look back and say, “Ah, that’s why that all happened the way it did. It makes sense to me now.”

Why? Because martyrs are bullshit.

You were never meant to be a sacrificial lamb. Your purpose in this life was never to endure pain simply to help lessen the pain others feel.

We tend to think big events have to have big causes, or big-picture plans, behind them. We want to believe, often desperately, that behind it all there’s a “reason”; even if it lies beyond our comprehension. And, when it comes to pain inflicted upon us, it’s often easier to believe we suffered for a cause than it is to claim the self-worth necessary to say we never should have suffered at all. But the latter is the only place true healing exists.

I believe there are two immutable truths regarding life-altering, early trauma. The first is that it was never your fault. And that’s something that can never be said enough to anyone who’s lived through any kind of early-life neglect or abuse.

But the second truth is that there was no purpose to it. It happened because the people you were entrusted to were fucked up in ways that more often than not extend back to a time when they were also young and defenseless.

That’s it. No purpose. No master plan. No “Usual Suspects” moment where all the pieces come together.

Terrible things happen sometimes because, for all the wonders of human achievement -from Mozart to Basquiat to missions into outer space- we’re still a species whose “kill or be killed” animal brain struggles to handle the complexities of modern human consciousness. The level we exist on is a little like handing a child just learning to drive a high-performance sports car and turning them loose on streets crowded with pedestrians.

There is purpose to the struggles that stem from our traumas -addictions and other self-destructive behaviors. But the fealty of that purpose is solely to oneself. They are born in innocence; just a means of basic survival. But they mature into struggles so that they can offer the opportunity for self-discovery and evolution. They are crucibles of change with a winner-takes-all choice attached.

If you choose to evolve with them, it’s tempting to look back and judge the experiences you’ve left behind harshly. You compare where you are to where you were and think, “I fucked up.”

But, if all wisdom and insight we gain in this life is built on what’s been gleaned from the experiences preceding it, then isn’t it more likely that the place you’re at now has come as a result of your so-called struggles than in spite of them?

We need to stop seeing better coping skills as the intervening army that stopped the warpath of self-destruction. That’s just creating mythology when the truth is more interesting.

Because the truth is one is just an evolution of the other. The metaphor of a caterpillar becoming a butterfly is about as cliche as one can get. But it feels apt here. Both are just different stages of a single life cycle.

Our struggles are never an interruption of life. They are just a necessary stage of a life cycle set in motion by circumstances we had no control over. And that can be a difficult thing to accept. But there’s liberation in it as well.

And so, to me, the danger in trying to assign “purpose” to terrible trauma through the work we do is that it just creates another dependency. It’s just one more thing outside ourselves we’re relying on to manage the pain.

I believe we can reframe our pain into something good. I believe in the power of that process. Acts of service and works of art are both good examples of this. But to be a practitioner of that particular alchemy, if we wish to practice it well, requires that we give from ourselves to the process while asking nothing of it in return. That’s the deal we make.

I think again of that question from across the table. “Otherwise, what would be the point of everything that happened?”

What if there was no point other than to have lived through it in order to arrive at the place we are? If our life has beauty here and now, isn’t that enough reason to be alive in this present moment? What if we let go of the notion that our next moments can somehow ever reconcile our previous ones and simply live them as complete entities unto themselves?

Maybe none of this is what his question was about. Maybe I’m reading my own story into it. But, if there is any sort of carry-over, I wonder, from this perspective, what decision would he make…

5.12.21

Dunning-Kruger… If you’ve spent even a modicum of your time in the fray of political firefights being waged ever since that last guy was in the White House, you’ve almost-certainly encountered the term. In all likelihood, you’re probably sick of it by now.

The Encyclopedia Britannica defines Dunning-Kruger Effect as follows: a cognitive bias whereby people with limited knowledge or competence in a given intellectual or social domain greatly overestimate their own knowledge or competence in that domain relative to objective criteria or to the performance of their peers or of people in general.

None of this is of interest to me right now. I want to know about the opposite.

What do we call it when people with an abundance of knowledge and competence underestimate their own abilities specifically because of how much they know, or how good they are? What’s the term for that?

While Ginsberg may have famously observed the best minds of his generation being destroyed by madness, I see some of the best of mine so often languishing in a kind of mental dysmorphia around how capable they really are. It’s a case of the proficient looking inwards and seeing barely-passing competence. It’s not the sense of ‘not belonging’ that so often goes with imposter syndrome. It’s the feeling that the only project worth sharing is the one that’s just ahead and currently out of reach. It says, “I know what good is and I’m still not there yet. I need to stay back in the shadows until I hit that mark.” It’s the voice that warns, “You only get one chance to make a first impression, so that first offering better be a fucking opus!”

As the world around us is slowly opening back up, there’s a lot of talk going around right now about what we’ve learned from our experiences during the pandemic; what, from this time, can we bring with us into the time ahead?

Personally, I would like to take a lesson from the virus itself.

Part of what has made COVID-19 so deadly is the sheer volume with which it replicates itself. At the rate it goes, mutations are unavoidable. Some mutate in a way that make them weaker and quickly die off. But others manifest as something more virulent and eventually become dominate over older versions. The California strain. The South Africa strain. Etc. All of it made possible by the sheer volume of output.

This is what I hope for those languishing best minds of my generation in the time ahead. This is what I’d like our ‘roaring twenties’ to be about: output.

Step away from your reverse-Dunning-Kruger, feel your competence, and say yes to everything. You’ve spent your life perfecting quality control. Trust in that and allow opportunity for quantity now.

JUST. MAKE. THINGS.

4.13.21

Notes from the pages…

I imagine there are any number of people among us who were given everything they needed in their formative years. I’m not talking about physical comforts; though I don’t take having had them for granted. I mean real emotional and psychological nourishment; like a plant growing in an ideal condition of sun, soil, and water.

I’ve known a few such people in my life, or at least people I believe to have come from such a place. And I’ll cop to envying their ease; their assuredness of their place in the world and their right to claim it. But I can’t say I’m that interested in their stories.

Hemingway once famously said, “The world breaks everyone.” I think, culturally, we might even be able to arrive at some sort of a quorum around that point. But, in doing so, what’s frequently lost is how early it so often happens -and how, once it does, it has a tendency to become the whole of your story for as long as you let it.

I’ve watched people, lacking either the perception to recognize it, the courage to see it, or some combination of both, contort themselves in any number of ways; trying to shape an inner and outer world-view that supports it.

Others recognize it but form a kind of Stockholm-syndrome attachment to it: allowing themselves to be slowly eaten away from the inside.

The weakest among us simply can’t hold it and erupt; raining hellfire around them and a trail of scorched earth in their wake.

All of these strategies are untenable in their own way. They all inflict varying degrees of collateral damage on life.

And so, I think there’s something inherently noble in the courage to enter the labyrinth that lies within you and search for the minotaur.

Leaning into the idea of archetypes, I’m drawn to the stories of katabases found in mythology. In many ways, they have been my story. In many ways they still are my story.

Entering the maze leads to only one of two outcomes. You can either succumb to the forces in your life that built it, or stand defiant against them and, in doing so, rediscover yourself.

It doesn’t matter the outcome. These are the stories that interest me. They are the greatest affirmations of a will to life I can think of.

4.01.21

The world will ask you who you are, and if you don't know, the world will tell you. -Carl Jung

I came across this quote the other night. I’m not one to go looking for signs. But I am attracted to synchronicity. And, with the assembling of this website commanding a lion’s share of attention at the moment, it’s hard to imagine a sentiment more in sync.

You could substitute, “the world”, in Jung’s statement with, “the (film) industry”, and it would hold just as true. Perhaps more so. The industry, after all, often seems to be locked in a red queen’s race with the world it perceives existing beyond its studio gates; running in place, forever a half step behind. Sometimes new ground is gained. But the widening of the aperture happens in fits and starts, with at least as many obstructionists as advocates.

Back in college, I had a professor who, between lectures on the Greeks, Shakespeare, and Pinter would do his best to pass along any wisdom he had of ‘the business’; offering it up with a sort of grandfatherly benevolence.

I remember him talking once of ‘type’ and casting. He began by verbally painting a picture of a burly, grizzled, and sun-weathered biker dude. Then, with the mental image fully established, he continued, “He may have it within him to play the most heartbreaking rendition of Romeo anyone’s ever seen. But he won’t ever be cast as Romeo. If he wants to work, he needs to accept that and harness whatever’s in him towards the roles he will be considered for.”

There were maybe only a dozen other students in the class. We were a few years into our college experience and, by that point, most of our classmates had bailed in favor of far more sensible areas of study than theatre. I watched the ones that had stuck it out with me all nod along with a reverence of understanding for the wisdom the professor meant to impart. I leaned back in my chair and thought, “That’s bullshit!”

The avenues and boulevards of this city are littered with storefronts-turned-studios where actors are being told to ask their peers to tell them what they see them as and then to accept what they hear as their ‘brand’.

“I see you as the know-it-all working the help desk at a Best Buy.” And, with that, the actor goes out shopping for a royal blue polo shirt to wear to auditions; their sense of self and capacity for story both limited because they’d paid an instructor to tell them to trust someone else’s perception, baggage and all, over their own inner voice.

We all have our stories to tell. And this whole hulking form of recorded storytelling that we do is only ever advanced when someone who’s been told no decides to bet on themselves instead of conventional wisdom.

I have nothing but fond memories of that professor. But, at the fork where I choose which path to walk down, I’m going with Jung’s. I’m here to tell the world who I am. That’s what all of this is about.

3.20.21

During my senior year in high school, a faulty bit of construction work from nearly two decades prior caused the back half of my family’s home to catch fire.

I wasn’t awake when it happened. A chance opportunity to go backstage at the Big Audio Dynamite concert the night before had seen my friend Dave and I push our curfews to their limits. That Saturday afternoon, I was catching up on my sleep.

“Jon! The house is on fire! We need to get out right now!”

The call came up the stairs to my bedroom. With little time, I made some quick decisions and ran down the stairs; exiting the house through the front door as the fire trucks were arriving.

In the end, the house was ok. The fire had been contained to the attic above the family room and was put out before doing any severe damage. Standing on our front lawn, I watched the firefighters stretch tarps over our charred and steaming roof while I held onto my guitar, my leather jacket, and my childhood Indiana Jones hat; the three things, in the split second decision of a crisis, I chose to save.

So why am I telling you this? Why now?

Because I think it’s illustrative of a greater truth. It’s about the way crises have a habit of laying bare to us the things we value most. In the split second I had to decide what to save from potential incineration, seventeen year-old me chose a symbol of my still-forming identity, a connection to the fondest part of my childhood, and a vessel for creativity. Crisis shows us where our heart lies. It’s there in the things we rush to protect.

When all is said and done, when all the evidence has been collected and analyzed, I have no idea what our final understanding of the tragedy that took place in Atlanta this week will be. But I do know this: if, in the wake of a rampage that left eight people dead, your first instinct was a rush to decry the media for being too presumptive in labeling the event a hate crime, you have made crystal clear where your heart lies. The simple fact is, in the crucible of the moment, the thing you rushed to protect was racism. And you need to own that.

3.11.21

On March 11, 2020, The World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus a global pandemic.

Recollections:

“Last dance!”

That was what we said on our way to a small club down the street from us in Hollywood a year ago today.

“Last Dance!”

It was an honorific we’d given the night without really having any idea of everything the declaration portended; without fully realizing how prescient it was.

Earlier in the evening, walking to Black Market Yoga, a ‘breaking news' banner flashed on my phone. Tom Hanks had just announced that he and has wife had tested positive for COVID-19. As uninformed and absurd as it seems now, this was the moment the virus stopped being something happening somewhere else. America’s Dad had been infected and, on that fact alone, the threat was no longer hyperbole.

Before class, talk of the news was buzzing all around. But it had more of a, “This is crazy”, quality to it than any real dread. The panic that would quickly metastasize into hoarding was still a day or two off.

By the time I left class that evening, other announcements had come through. The government was shutting down flights from Europe. The NBA was suspending its season.

Back at home, Lauren, Jenny, Magda and I tried to understand what it all meant. Los Angeles county announced it was prohibiting gatherings of more than 250 people; a threshold that was certainly high enough to accommodate the club Magda was playing later. It was a Wednesday after all. But what about the other party she was set to play on Saturday? What was going to happen? I retrieved the door-clicker I still had from my own days of throwing parties and humorously volunteered to make sure the threshold was upheld, with an ad lib impersonation of a door person. “248… 249… 250… and scene!” I brought my hands down pantomiming a gate crashing shut. We all laughed. But it was a nervous kind of laughter. “Last dance!”, we said and started off for the club.

There’s a strange and uneasy energy that’s made when apprehension and denialism vie for dominance and, in the few blocks we walked, that energy felt like it was rising all around us; like water slowly filling a car that had careened off the road and into a river. Jenny talked about flying to Hong Kong. She wanted to get to where her parents were while she was still able to book a flight out. I nodded along to what she was saying, but I silently wondered if she was overreacting. “We still don’t know anything yet.”, I told myself. And of course I did. For better or worse, in the story of the ant and the grasshopper, I’m perennially siding with the grasshopper. By Friday evening, Jenny would be in a car on her way to LAX. By July, most other countries in the world would be refusing Americans entry. Refusing Americans entry… in our collective national hubris, I wonder if we ever allowed for a reality where those words would occupy the same sentence.

At the club, Magda settled into her set while Lauren and I headed for the dance floor. I suddenly found myself hyper aware of personal space in a way I never had before. It’d been thirty years since I’d used a fake ID to go to my first club. The environment was a second home to me. I’ve lived for the revelry of nights in packed sweatboxes. There was ample room that night. But, still, people couldn’t stay far enough away for my comfort. I moved to the side, away from the dance floor. It was the beginning of a feeling that would grow in the weeks ahead; the feeling that every strange face could be an unknowing murderer. Sadly, it would be the exemption of familiar faces that would end up creating the largest outbreaks in the year ahead.

Later, as the club emptied out onto a side street at 2am, Lauren and I watched a group of early twenty-somethings try to figure out where to go next. Lauren said she felt sorry for them; to have such important and influential years upended by something like whatever was coming. I saw myself at that age; the long nights shoulder to shoulder in a pitch-black room, glimpsed only in fragments with the flash of a strobe, while music pummeled all thoughts save those of the moment out of our conscious minds. I saw myself crammed next to twelve other sleeping bodies on the floor of a tiny one-bedroom apartment in New York while we produced a play. I tried to imagine these moments gone. I couldn’t.

“It’s ok.”, I assured Lauren. “They’re just trying to get ahead of it. If everyone does what they need to now, it’ll all work out. It’ll seem a little weird for a few weeks; maybe even a couple months. But things’ll get back to normal before the summer. You’ll see. Don’t worry.”

And with that, we said goodnight to Jenny and Magda and made the short walk home.

3.09.21

There’s a line from the movie, Garden State. Someone asks Zach Braff’s character why he became an actor and he replies, “Because the only thing I’ve ever wanted to be was someone else.”

I may be paraphrasing. I don’t remember the actual exchange between the characters anymore. I’ve spent too many years internalizing it; believing it and making it my own.

When I first heard the line I was stunned at how succinctly it seemed to sum up my own life experience. “The only thing I’ve ever wanted to be was someone else”. That’s me. That’s why I’m an actor -or, at least that’s the story I told myself (and others) for a long time. I don’t anymore. I realize now that, in allowing that to be the story I told, I overlooked a pretty significant part of my actual story.

It’s said that all the best lies contain elements of truth. And the truth in this is that there were various versions of that story that were told to me throughout my early years; the story that I was disposable; a nuisance; unwanted; did not belong and “less than”. And, when those are the messages you receive when you’re young and defenseless, the leap to wanting to be someone, anyone, else isn’t a big one. But it’s a leap I never made.

I played a lot with artifice and archetypes in my adolescence. But I was never searching for an escape route away from who I was. I was looking for a trojan horse.

The secret truth is I’ve never wanted to be anything other than exactly who I am. I just didn’t think other people felt the same way; even as I held onto the certainty it was them, not me, who had it wrong.

I’m stubborn and uncontrollable and I wasn’t going to change for anyone. So a better strategy seemed to be to look for ways to slip past the sentries and let myself out under the cover of night. In this way, I learned to read the room, understand what people wanted to see, and reflect it back to them. It’s a skill-set that runs parallel to acting and, when practiced regularly, will allow you to pass handily as a competent actor. But it will never make you a good one.

That’s the rub of that scene from Garden State. It’s the problem with trojan horses. At its best, this trade isn’t actually about deception. It’s a staredown with the truth and a refusal to be first one to look away. And It’s only when you stand before the gates undisguised, out in the open as yourself, fully, defiantly, and unapologetically, that you have anything to say that’s worth a damn.

3.04.21

This is a test. This is only a test.